| |

| My Trip to Xibalba and Back |

"Maya Caves of West-Central Belize" June 2000 |

| Text and Photographs by Amélie A. Walker | |

|

My first days in Belize were spent digging at Cahal Pech, a surface site in San Ignacio. Having participated in a Maya excavation before--at the nearby site of Baking Pot in 1996--I found it to be familiar, even comfortable. Then I went into the deep jungle, where for the next two weeks I would explore caves the ancient Maya believed were portals to the underworld, Xibalba. |

Having a pre-jungle Belikin, the local beer |

I started at the relatively luxurious Che Chem Ha Camp (Camp 1 on the map) near the cave of the same name, previously excavated by the Western Belize Regional Cave Project (WBRCP). The camp has running water pumped up from the river for showers and sinks. Outhouses are placed at the back of camp, up a hill away from the living areas. (As they are a bit away from camp, it was advised to take a machete on the way up to use in case of snakes.) Students and staff sleep in tents or in hammocks strung in a thatch-roofed champa. After setting up my hammock, I noticed large holes in my mosquito netting, which a teammate expertly mended with duct tape (always useful in the jungle). Food here is wonderfully prepared--some of the best I had during my stay in Belize--by a local woman who takes care of the camp. We even had heart of palm soup one night as an appetizer.

Tents at Che Chem Ha Camp |  Relaxing in the hammocks |

We rose bright and early at 5:30 am, ate our breakfast, then piled into trucks for a short ride down the road to where we hiked up to the caves. On my first day I set out for the cave Chapat. Our trek up the hill through the jungle briefly went into reverse when one of our group spotted a fer-de-lance, a highly poisonous snake, on the path. After it was beheaded with a machete, we continued our journey up to the cave. We stopped at its mouth to admire the view, strap on our helmets and head lamps, and to hear a few rules. This was my first real experience spelunking, and my pulse quickened. We were led into the darkness by Josalyn, the supervisor of work at Actun Chapat, to Chamber 3, where excavation was to take place. I made my way, stumbling over a few rocks, with only a cut thumb to show. Besides our individual helmet lamps, there were other lights used in the cave--one propane and another battery-operated (referred to by the group as "the sun"). Units were set up and excavation began.

I was shown briefly into Chamber 4. Once walled up by the Maya, it had been broken into by looters who left behind smashed pottery and pits. Right, Josalyn points out broken pottery left in Chamber 4. |  |

The next day I was off for Actun Halal, affectionately called Actun "Long Haul" by those working there. The hike is indeed a long one, with some tricky cobblestones and heart-rate elevating hills. This cave was very different from the nearby Chapat, in that it is almost entirely in the light zone--there are two entrances and one can be seen from the other. For this reason, many are inclined to call Halal a rock shelter. Cameron, co-director of the WBRCP and supervisor of excavations at Halal, says it is a cave.

In Halal, there are a number of faces carved in the flowstone walls. I must say I had a hard time making them out, though some--such as the large face--are impossible to mistake as anything but intentional modification of the rock.

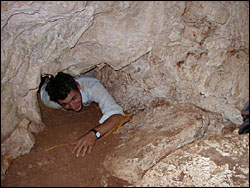

| A small side chamber was explored, one person almost getting stuck. It was thought a passage led in further, but this was found to not be the case. A dead end... Left, squeezing out of the small chamber in Halal |

The next day I was driven to Barton Creek Cave. My ride was two-and-a-half hours late, but that was nothing to be concerned about. I was on Belize time, people kept telling me, not New York City time. It took only about 45 minutes bumping along a shortcut through an orchard and a Mennonite community to arrive at camp (Camp 3 on the map).

Canoeing into Barton Creek Cave

Helmet on, I got into the canoe and was paddled into Barton Creek Cave. Quiet, only the sound of our paddles in the water. I happily looked around, feeling myself slip into imaginings...until my headlamp went out. I fumbled in the near-darkness for new batteries, inserting them to no good result. As we had reached our destination, I shoved my dead lamp in my bag and gratefully accepted the loan of a working one.

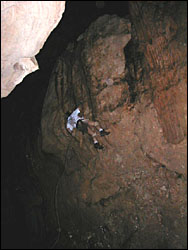

I climbed out of the boat and up the rock, where I was given a harness for my rapell down to access the ledge where they were excavating. On rope, I backed over the ledge of the cliff and began easing myself down. It had been six years since I had been rock climbing, so this was quite a thrill. There was a scare as one of my braids swung forward to get tangled in the ropes--I tied my hair securely in the back ever after--but I eventually made it to the "Maya Bridge" (the name tour guides use to describe the ledge that connects the cave walls over the river) and detached myself from the rope. Each person rapelling down had to be careful of a skull placed on the middle of the bridge for the benefit of tourists, who are canoed through the cave regularly on tours. Right, rapelling onto the ledge |  |

Up on the ledge where investigation was taking place, I saw before me a pit full of human bones. The group did a surface collection, tagging the bones for removal, then began to excavate. At the end of the work day, we each had to rapell again, this time from the bridge into the river and a waiting canoe, if we were lucky, underneath.

It is amazing to think of the ancient Maya making this same journey into the cave for this material to be here in the first place. How did they do it without the modern equipment we found necessary to reach the ledges?

The next week saw me to the jungle camp in Roaring Creek Valley (Camp 2 on the map), called the "Xibalba Hilton" by the archaeologists. It is impossible to drive into camp, so we hauled all our gear into the jungle, hiking for about 45 minutes to reach the camp, which sits on the river that runs into Actun Tunichil Muknal. This camp is the most rustic of those used by WBRCP. There is nothing resembling running water--the river serves as both drinking water (gathered at the mouth of the cave) and for bathing (downstream). The fare at jungle camp is mostly beans, rice, and tortillas, always waiting for us as soon as we woke in the morning and when we arrived back from the cave each night.

The lab at Roaring Creek Valley Camp

WBRCP is currently investigating Actun Nak Beh, about a 20-minute hike through the jungle from camp. The tour of the cave did not last long, as we discovered we needed ropes--they had been removed for the weekend--to safely continue. The next day we had webbing secured so that we could descend further.

| There are some unique concerns when excavating in caves. First of all, everything is just a little bit more difficult, as much work takes place in very small spaces (see Student Journals). One real hazard is histoplasmosis, a lung disease contracted by breathing in spores that grow in bat guano. Masks (left) must be worn to protect against this. Then there are the assassin bugs, whose bites can carry the parasite that causes Chagas' disease. Many fell to a trowel while I was at Nak Beh. |

After a long day working at Actun Nak Beh, we entered Actun Tunichil Muknal, a cave with a stream running from it, at night. Time does not matter when you are going into darkness. With a gasp, I plunged into the cold water. My dry bag with my camera and a number of others' safely inside, bobbed on my back. Following our guide Christina, one of the graduate students who has been with the project for a number of years, we worked our way into the cave, over large rocks, climbing through tight passages, often waist-deep in water. We passed the area underneath the stelae chamber where underwater excavation was taking place and were cautioned not to go over it as we might damage equipment. We reached a ledge where everyone was required to take off their shoes, as to not damage the artifacts embedded in the cave floor's flowstone. Continuing on in our wet sock feet, we passed and inspected full vessels which had been claimed by the cave and many human bones and skulls.

A complete jar nestles permanently in the cave's formations.

We reached a wide open cavern, referred to as the "Cathedral" where stalagmites rose and stalactites fell as far as our lights reached and beyond. We then climbed up to the chamber where the calcite-covered skeleton of a woman lay, unfortunately some of the calcite had been rubbed off one of the leg bones recently by an unknown visitor. Having reached the extent of our journey within, we turned and retraced our steps, awed by the cave that had been used for ritual purposes by the Maya long ago.

I returned for a quick night bath in the river, then crawled under the mosquito netting and into my hammock. Another full day in the jungle of Belize, exploring the Maya underworld.

Amélie A. Walker is an online editor and the webmaster of ARCHAEOLOGY.

Intro | Trip to Xibalba | Interview | Field Notes | Student Journals | Remote Sensing | Q&A | Map

Advertisement

Advertisement