Rusty Peterson taking a fisheye photograph. These photos can be used to determine percentages of canopy cover. |

Over the past weeks we have visited sites in several areas of central western Belize, including the Macal River Valley, the Roaring Creek Valley, the Barton Creek Valley, and the Caves Branch area, as well as a new cave south of San Antonio. This broad survey has yielded data on a variety of cave types and contexts, as well as a broad geographical distribution of caves. This update features the caves we visited in the Macal River Valley.

Cave: Contreras Sinkhole

Crew: Cameron Griffith, Rusty Peterson, William Pleytez, Rock Ortega (assistance and consultation provided by the Minanha Regional Survey, Sam Connell, principal investigator)

The RSP crew entering Contreras Sinkhole |

We hiked into the Macal Valley in search of the field camp of the Minanha Regional Survey (MRS) archaeological project. After a two-hour slog over a muddy road though the jungle we met up with archaeologists Sam Connell and Ted Neff, who kindly directed us to a large sinkhole near a small group of surface structures that they were excavating. The MRS research area and the sinkhole are located on the northern end of the Vaca Plateau. The sinkhole was named Contreras Sinkhole after landowner Enrique Contreras.

| Contreras Sinkhole is particularly interesting for the remote-sensing project, because it is located in the middle of a milpa. Because of clearing for the planting season, there is essentially no forest canopy near the feature. Only a few cohune palms grow amid the cornfield, which in previous years has also been planted with beans. Thus the vegetation composition in the area is quite basic, and there is no canopy to interfere with any temperature differential created by the air emanating from the sinkhole. Left, measuring the height of corn in a milpa to help with remote sensing classifications. This corn was 3.25 meters (10 1/2 feet) tall! |

The team rappelled 22 meters (72 feet) to the bottom of the sinkhole and discovered that it is merely a cylinder with no branching passages or tunnels. The lack of a significant horizontal subterranean component may be the reason why there is little difference in the temperature of the air coming from the sinkhole versus the surface environment around the entrance.

Cave: Serpent Cave

Crew: Cameron Griffith, Rusty Peterson, William Pleytez, Kimo Jolly, Henry Badilla, Molly Sandgren, Matt Kalch

Serpent Cave has a large horizontal entrance that quickly closes down to a tube less than a meter in diameter. Although it had been extensively looted, this cave had not been archaeologically investigated. There was dripwater activity in the entrance of the cave at the time of our visit which created a small pool. This hydrological activity may only be seasonal in Serpent Cave. Comparisons of satellite images of Serpent Cave during dry conditions versus wet conditions could help us locate caves with similar hydrology.

Cave: Stelae Cave

Crew: Cameron Griffith, Rusty Peterson, William Pleytez, Kimo Jolly, Henry Badilla, Molly Sandgren, Matt Kalch

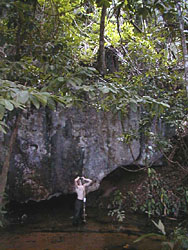

The entrance of Stelae Cave |

| This cave, like Serpent Cave, had not been explored by archaeologists. After recording remote-sensing data outside the large horizontal entrance, we explored and mapped the cave. Although this cave had been looted, the archaeological remains we encountered were very impressive. Stelae Cave boasts a monument 2.9 meters (9 1/2 feet) long, pottery caches, and architecture. In this cave the ancient Maya were modifying the stalagmitic formations to create eye-holes. It is possible that they were then backlit by torches to provide an eerie effect, similar to that of a modern Jack-o'-Lantern. The cave also has two negative handprints that were produced in the same fashion as those in Actun Uayazba Kab. Left, William Pleytez and the stela in Stelae Cave |

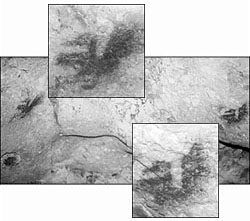

| Right, two negative handprints on the wall of Stelae Cave. Note that both were made with the person holding both hands together and interlocking or touching the fingers together. |  |

Cave: Crystal Pit Sinkhole

Crew: Cameron Griffith, Rusty Peterson, Bruce Minkin, William Pleytez

William Pleytez, who grew up in the Macal Valley, led the team to another sinkhole. William informed us that the sinkhole had been dubbed the "Crystal Pit" and that it appeared to have subterranean passageways. The area around the entrance was burned by a fire that in late April-early May of this year raged uncontrolled over a large area in the Macal Valley. As a result of the fire, there is only meager vegetation below the broken canopy. Considering that this cave has a substantial dark area this site creates a situation that will be interesting to observe in the thermal bands because of the light vegetation cover.

The entrance of Crystal Pit Sinkhole |

William pointed out several species around the entrance of the Crystal Pit that are favored by bats such as heart plum, fiddlewood, wild cherries, black chechem, trumpet trees, and rumon (breadnut). Wild cherries were most abundant followed by heart plum, fiddlewood, and trumpet trees.

The Crystal Pit had not yet been visited by the WBRCP, so a brief reconnaissance of the cave was necessary. The team rappelled 28 meters (91 1/2 feet) to the bottom of the sinkhole, and, as we suspected, there are a number of subterranean rooms and passages in the cave. Directly under the sinkhole there is architecture in the form of terraces or steps that lead down into a large room. We soon discovered that the Crystal Pit was aptly named--the chambers within are filled with beautiful, sparkling aragonite formations that glow bright orange when you backlight them with your flashlight. The Crystal Pit contains human skeletal remains, potsherds, burned wood, and an abundance of charcoal and ash. A sketch map was made and the artifacts tabulated. The WBRCP may investigate this cave further in future field seasons.

Cave: Actun Che Chem Ha

Crew: Cameron Griffith, Rusty Peterson

Actun Che Chem Ha (Poisonwood Water Cave) was investigated by the WBRCP in the 1998 and 1999 field seasons. William Pleytez's family members are the stewards of the cave. William's mother and brother, Lea Castellanos and Gonzalo Pleytez, lead tours through Che Chem Ha. The cave has a small horizontal entrance (less than one meter in diameter) half way up a large limestone karst hill. The size of the entrance makes it unlikely that it will produce a significant thermal differential. This cave exhibits animal activity that, if our hypothesis is correct, will affect the vegetation in the cave entrance microenvironment. According to William this hillside was also subject to the same burning episode in May of 2000 that claimed the understory around Crystal Pit sinkhole. This may provide another interesting comparison.

Cave: Actun Chapat

Crew: Cameron Griffith, Rusty Peterson, Bruce Minkin

Since the WBRCP had already conducted research in Actun Chapat in the 1999 season and in June of 2000, our objective was only to conduct the remote-sensing research. Actun Chapat translates as "Cave of the Centipede." The cave has two entrances, a sinkhole entrance and a horizontal entrance. On the first day we collected the remote-sensing data at the sinkhole entrance. While smoking a cigarette on the downhill edge of the sinkhole, we noticed the smoke being pulled into the hole. This is a phenomenon that a fellow project member, Mike Miro, had mentioned to the group as a feature specific to certain caves. While we were watching the smoke travel down into the sinkhole entrance the airflow suddenly reversed and the cave blew air out with strength comparable to the inflow a minute before. After only seven minutes of blowing the cave returned to sucking air. This sort of phenomenon certainly affects the thermal environment of a cave entrance. As a result of this experience our protocol includes recording the airflow at cave entrances as an element of the remote-sensing data.

We returned to the cave the next day to record remote-sensing data at the other entrance. This is a large horizontal entrance with a streambed that leads to an arroyo. While we were at this entrance it was dry, but when the cave floods the streambed and arroyo fill with water. We negotiated our way down the overgrown, boulder-filled streambed using tape and compass to determine the position of a thermal logger (the canopy was too thick to get a GPS reading on the logger). While moving through the streambed we noticed an abundance of pacaya palm. This bed is also rife with a plant that William calls the "110 volt electric plant." We do not yet know the scientific name for this plant but we are comfortable with the local name. If the tiny spines of this plant touch your skin it feels like an electrical shock! As a result of our numerous personal encounters with this plant we named the streambed "Electric Avenue," in the spirit of Eddy Grant's pop hit. Dominance of certain species such as the pacaya palm in a microenvironment such as the streambed is precisely what we believe will show up in the multispectral and infrared bands of a satellite image. Right, the second entrance of Actun Chapat |  |

Cave: Son of Chapat

Crew: Cameron Griffith, Rusty Peterson, Bruce Minkin, William Pleytez

The one known entrance of Son of Chapat is similar in morphology to the horizontal entrance of Actun Chapat. This cave also floods, and when it does the water feeds into the same arroyo as the water from Actun Chapat, but a few kilometers up the arroyo. William Pleytez lives only a few kilometers away from these caves and over the years he has witnessed many flooding episodes in the area. He reported that water literally shoots from the entrance of Son of Chapat into its streambed. On our way to Chapat and Son of Chapat we walk through this arroyo. It is obvious from the large piles of brush and the absence of large trees that this arroyo carries a substantial volume of water during the flooding episodes that occur quite frequently during the wet season. If we are able to pinpoint the dates of flooding in Son of Chapat we may be able to further define a spectral signature for caves that emit water either periodically or with regularity.

Cave: Actun Halal

Crew: Cameron Griffith, Rusty Peterson, Bruce Minkin, William Pleytez, Matt Kalch, Kimo Jolly, Henry Badilla, Anh-Thu Cunnion, Lauren Tobias

|

Actun Halal is located between Actun Chapat and Son of Chapat, only 100 meters (327 feet) from the entrance of Son of Chapat. It is morphologically quite different than these caves, however. It has two large horizontal entrances that are only 40 meters (131 feet) apart as well as a minor dark-zone component. This cave does not flood and does not have a streambed like the other two nearby caves. This close proximity to the other caves coupled with the morphological difference should provide an interesting comparison when we look at this area with the satellite images. We monitored temperature at Actun Halal and Son of Chapat concurrently. This should also make for an interesting comparison when we analyze these data. Left, the remote-sensing crew in Entrance 2, Actun Halal. |

Advertisement

Advertisement