Why do fakes get made? Why do people fall for hoaxes? Greed, pride, revenge, nationalism, pranks, and gullibility mix in an archaeological setting

There's no avoiding it--fakes are everywhere. Jane Walsh of the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History says, "any museum--I don't care what museum it is--has fakes." While some hoaxes have humorous elements, this is a serious problem. Fakes pollute the archaeological record and skew our understanding of the past. The infamous Piltdown Man, which matched conceptions of what an early hominid should look like, misled scientists for decades. Crystal skulls were first faked in the later 19th century, when little was known about Mesoamerican religious practices. Today, they are still taken as real by many people. Biblical artifacts, faked or enhanced with inscriptions, play on peoples' religious beliefs.

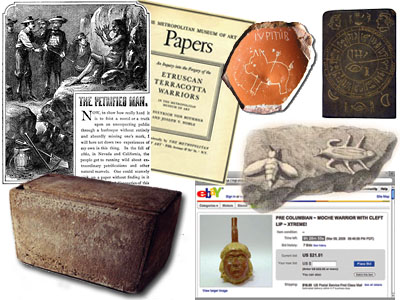

Bogus artifacts vary in subject and complexity. The Cardiff Giant and similar petrified men involved only the crudest technique, while the Tiara of Saitaphernes is the work of a gifted goldsmith. They come with a range of price tags. There are low-cost ones on eBay and million-dollar ones, as the Getty kouros may be.

The reasons for perpetrating hoaxes and forgeries range as widely as the kinds of fakes. Common motives for making bogus artifacts include publicity and self-promotion, monetary gain, practical jokes, and revenge, but some fakers have had the goal of supporting their own theories about the human past. Fakes have often been inspired by nationalism, with patriotic perpetrators boosting their country through spurious links to past civilizations.

People are taken in by hoaxes and fakes for many reasons. Successful bogus artifacts often match expectations or preconceived ideas of antiquities. Spectacular fakes have worked because those who buy them are blinded by their own pride of ownership--and the higher the price tag, the harder it is to make an embarrassing admission that it's a fake.

Problematic artifacts are possible only when the importance of regulated, documented excavation is ignored. Acquiring artifacts lacking a reliably documented find spot not only fuels the looting of archaeological sites, but also opens the door wide for the introduction of fakes. Archaeology depends on controlled excavation and meticulous study. By ignoring the due process of research, individuals and institutions have exposed themselves to deceit and, at times, ridicule.

At the same time, archaeological research can spur the creation of new kinds of fakes. For example, Kenneth Lapatin, in Mysteries of the Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, and the Forging of History, describes how excavations in Crete led to the development of a new type of fake. When discoveries are published, interest in a new area of material culture can encourage production of such pieces. Where there's a market, there's a fake.

The eight classic fakes and hoaxes here have been selected for various reasons, including how long they fooled the public and experts, the technical skill employed, their impact on scholarship, and the motivation of their creators. Famous fakes, such as the Shroud of Turin, have been omitted, not because they are not important but because they often overshadow other, equally interesting cases.

Fakes and hoaxes are not new. Kenneth Lapatin says "The earliest known fake to me is a second-millennium B.C. cuneiform inscription purporting to be a third-millennium B.C. original that ascribes ancestral privileges to Babylonian temple priests." It is now in the British Museum. Fakes will continue to be made as long as people are willing to buy artifacts with no background. Hoaxes will continue to be perpetrated as long as people try to play practical jokes, humbug the gullible, or embarrass rivals. And scholars will continue to root old ones out of museum collections.

Brittany Jackson is a student of anthropology at the University of Chicago. Mark Rose is AIA Online Editorial Director.

- See all of our coverage of Hoaxes, Fakes, and Strange Sites.

Advertisement

Advertisement