Who Made the Shroud of Turin?

by Heather Pringle

January 29, 2010

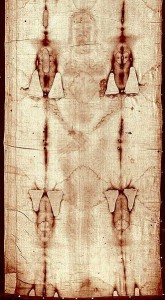

If you are not Catholic,  you  may not have heard yet that the Vatican has decided to put the very famous Shroud of Turin on public display for six weeks, beginning on April 10th.  Exhibitions of the controversial shroud–believed by many devout Catholics to be the winding cloth that covered Jesus after his crucifixion–are relatively rare. Indeed, the Vatican has authorized only five such expositions since 1898.  As a result,  the faithful are hastening to their computers to obtain online tickets.

If you are not Catholic,  you  may not have heard yet that the Vatican has decided to put the very famous Shroud of Turin on public display for six weeks, beginning on April 10th.  Exhibitions of the controversial shroud–believed by many devout Catholics to be the winding cloth that covered Jesus after his crucifixion–are relatively rare. Indeed, the Vatican has authorized only five such expositions since 1898.  As a result,  the faithful are hastening to their computers to obtain online tickets.

I notice that the Vatican will not permit any scientific experimentation or testing of the shroud during the exhibition.  Quite possibly,  it is a little disenchanted with the latest archaeological findings related to the controversial cloth.  In December,  Shimon Gibson, an archaeologist and senior research fellow at the W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jersualem, announced tantalizing results from a new study that he and Boaz Zissu,  an archaeologist at Bar Ilan University, just completed on a 1st century B.C.  shrouded burial they excavated in a tomb in Jerusalem.  Gibson and several colleagues published the first part of the study in a paper in PLoS One on December 16th.

The entire study will clearly shed much new light on the authenticity of the more famous Shroud of Turin.  As the team points out in the PLoS One paper, archaeologists rarely find ancient shrouded burials in the Jerusalem region:  the city’s high levels of humidity quickly destroy organic materials.  So,  as Gibson recently explained to a reporter at The Catholic Review,  “this  is the first shroud from Jesus’ time found in Jerusalem and the first shroud found in a type of burial cave similar to that which Jesus would have been buried in,  and (because of this) it is the first shroud which can be compared to the Turin shroud.â€

Gibson and his colleagues radiocarbon-dated the tattered vestiges of the excavated shroud to 95 B.C.E . Â And their careful examination revealed that the mourners in question employed two very different pieces of cloth to wrap the unknown dead male. They wrapped the individual’s head in linen cloth, Â and his body in wool cloth–a practice that Gibson says was part of traditional Jewish burial practices at the time. Â Moreover, Â this practice fits with the biblical description of the two pieces of cloth that Jesus cast off after he rose from the dead. Â The Shroud of Turin, Â by comparison, consists of just one large piece of cloth said to have covered both the head and body of Jesus.

And Gibson and his team found another critical difference.  The tattered cloths they excavated were woven very simply,  with a two-way weave.  The  Shroud of Turin, however,  exhibits a more sophisticated weaving pattern,  known as a twill weave.

No one will be able to draw any definitive conclusions about the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin based on this new study.  The comparative sample size is miniscule, and archaeologists  need to see much more in the way of Jewish burial shrouds from the period in order to establish what the customs really were.  However,  this evidence is the best we have at the moment,  and it certainly casts a lot of new doubt on the Shroud of Turin.

I’d like to join the pilgrims who will flock to Turin this spring, Â just to see the famous shroud for myself. Â But the big question in my mind is who made this fabled cloth?

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our