The Wrangling over Darwin’s Home

by Heather Pringle

February 13, 2009

Â

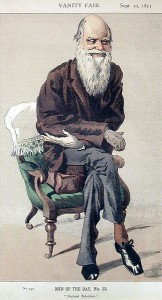

In his quiet country home near the town of Down, Charles Darwin penned one of the most influential scientific works of the nineteenth century, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, a book that would stir intense controversy among many of his contemporaries and inspire physical anthropologists and archaeologists for decades to come. Darwin marshaled his arguments carefully, proposing that modern humans and Africa’s great apes descended from a common ancestor, and he wrote with such transcendent beauty that his prose still resonates powerfully  today.  Â

In his quiet country home near the town of Down, Charles Darwin penned one of the most influential scientific works of the nineteenth century, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, a book that would stir intense controversy among many of his contemporaries and inspire physical anthropologists and archaeologists for decades to come. Darwin marshaled his arguments carefully, proposing that modern humans and Africa’s great apes descended from a common ancestor, and he wrote with such transcendent beauty that his prose still resonates powerfully  today.  Â

“Man,†Darwin concluded, “with all his noble qualities, with sympathy which he feels for the most debased, with benevolence that extends not only to other men but to the humblest living creature, with his god-like intellect which has penetrated into the movements and constitution of the solar system—with all these exalted powers—Man still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origins.â€

Darwin’s stature as a scientific thinker seems only to grow with each passing year, a fact attested by the current worldwide celebrations of the bicentenary of his birth. And yet some very curious wrangling is going on behind the scenes. When the British government applied to UNESCO two years ago for a designation of Darwin’s country home as a World Heritage Site, officials there apparently warned that it might not meet the organization’s criteria for scientific sites. Chastened, the British government withdrew its application. But it has now stubbornly resubmitted it. Â

I find this all extremely puzzling: Darwin’s home, Down House, would make a superb World Heritage Site. Darwin and his family resided there in a rambling Victorian villa for forty years, during which time, the naturalist wrote his most famous work, On the Origin of Species. The house still stands and the grounds remain the living laboratory that Darwin so loved.  It was at Down House that he observed earthworms and bees, studied insect pollination and tried to crossbreed pigeons—subjects that he later wrote about and that greatly influenced his ideas. Moreover, the grounds contain a beautiful wood  intersected by Darwin’s famous “Sand-Walk,† where  the natural historian frequently paced as he worked out complex details of his theories.  Â

The house itself has been restored by a public agency, English Heritage, and visitors can ramble through the rooms where Darwin, always the scientist, conducted some of his more odiferous research.  In 1873, for example, he obtained a collection of pigeon skeletons there by boiling down their carcasses.  “The smell was so dreadful,†Darwin confessed, “that it made me wretch awfully.â€

Although I have yet to see the house myself, I understand that it reveals many wonderful details of Darwin’s private life – things that help us imagine who this great thinker was as a man. Darwin’s restless curiosity about the world did not take kindly, for example, to being shackled to a stationary desk.   He had a chair fitted with wheels, so he could move about, and slung a board across its arms for a writing surface.  That was where he penned his most famous books.Â

I think this petty bickering over the letter of the law, when it comes to designating World Heritage sites, misses the real spirit of it in the case of Darwin’s home. If Down House isn’t part and parcel of our essential World Heritage, then I scarcely know what is.Â

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our