The Spirit of Egypt

by Mark Rose

October 23, 2009

Our special Egypt issue is now with the printer! While working on it, I took some books off my shelf and read what various 19th-century travelers and ex-patriots said about Egypt and the emotional impact its monuments had on them. Of course I turned to Mark Twain’s Innocents Abroad (1869) first. Surprisingly, the humorist was overawed by the Sphinx:

After years of waiting, it was before me at last. The great face was so sad, so earnest, so longing, so patient. There was a dignity not of earth in its mien, and in its countenance a benignity such as never any thing human wore. It was stone, but it seemed sentient. If ever image of stone thought, it was thinking. It was looking toward the verge of the landscape, yet looking at nothing—nothing but distance and vacancy. It was looking over and beyond every thing of the present, and far into the past.

If ever image of stone thought, it was thinking. It was looking toward the verge of the landscape, yet looking at nothing—nothing but distance and vacancy. It was looking over and beyond every thing of the present, and far into the past.

But he recovered himself and penned a long—and pretty funny—account of climbing the Great Pyramid. Flaubert, who visited Giza in late 1849 when he was only 27, had a similar reaction to the Sphinx:

The sand, the Pyramids, the Sphinx, all gray and bathed in a great rosy light; the sky perfectly blue, eagles slowly wheeling and gliding around the tips of the Pyramids. We stop before the Sphinx; it fixes us with a terrifying stare.

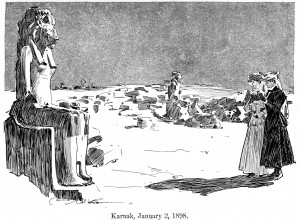

By March, Flaubert was tired of it all, writing, “the Egyptian temples bore me.†Yet, six weeks later, as he traveled north on the Nile leaving Egypt, he described Luxor as “incomparable in its effects of ruins in a landscape.†And then, “Karnak seems to me more beautiful, more grand than ever. Sadness at leaving stones. Why?â€

Florence Nightingale, in Egypt the same time as Flaubert, gushed about most of what she saw, giving her imagination and prose free rein. On New Years 1850 she went from Karnak to Luxor after dark:

…a little farther, a gleam of moonlight shining out, we saw on either side a ghostly avenue, gigantic sitting sphinxes, with their faces toward us, nearly as close as they could be placed, but most of them headless, limbless, or overthrown. The intellectual and physical force (there typified) lay in the dust. Its body, that is, lay there,—its spirit had vivified the world.

In Nightingale’s description, ghostly pharaohs populate the Valley of the Kings:

The “Valley of the Kings!â€â€”what a scene that name conjures up now in our minds of the great ones of the earth, not lying at rest, but stirred up to meet another at his coming.

In 1862, Lucie Duff Gordon moved to Egypt because of consumption. She died there in 1869, but left behind many letters that tell of life among the Egyptians, rather than about the tourist crowd or ancient wonders. She and her husband numbered among their friends Thackeray, Dickens, and Tennyson, so her letters are quite well written. In one of the few descriptions she gives of Egyptian antiquities, she writes:

I went last night to look at Karnak by moonlight. The giant columns were overpowering. I never saw anything so solemn.

Gordon’s spare writing contrasts with Nightingale’s slightly florid picture of the same night scene. Between the two is Amelia Edwards, whose A Thousand Miles up the Nile (1888) transcends the usual 19th-century tour account in her command of Egyptology, observation of local life, and quality of writing. Here is her description of Abu Simbel with its colossal statues of Ramesses II:

The great statues towered above their heads. The river glittered like steel in the far distance. There was a keen silence in the air; and towards the east the Southern Cross was rising. To the strangers who stood talking there with bated breath, the time, the place, even the sound of their own voices, seemed unreal. They felt as if the whole scene must fade with the moonlight, and vanish before morning.

They showed unearthly enough by moonlight; but not half so unearthly as in the grey of dawn. At that hour, the most solemn of the twenty-four, they wore a fixed and fatal look that was little less than appalling. As the sky warmed, this awful look was succeeded by a flush that mounted and deepened like the rising flush of life. For a moment they seemed to glow—to smile—to be transfigured. Then came a flash, as of thought itself. It was the first instantaneous flash of the risen sun. …and the colossi—mere colossi now—sat serene and stony in the open sunshine.

Every morning I waked in time to witness that daily miracle. Every morning I saw those awful brethren pass from death to life, from life to sculptured stone. I brought myself almost to believe at last that there must sooner or later come some one sunrise when the ancient charm would snap asunder, and the giants must arise and speak.

It is interesting that Edwards has several of the same reactions as the others. She is as overawed by the colossi as Twain and Flaubert were by the Sphinx. Her description of the dawn light as the flush of life on the statues and her feeling that the statues might rise and speak are mirrored in Nightingale’s thought of the dead pharaohs in the Valley of the Kings arising. Like Gordon and Nightingale, she experienced a heightened response to the monuments when they were illuminated by moonlight.

The impression made by Egypt on all of these authors was profound, and their accounts suggest they felt a greatness and timelessness, solemnity tinged with awe, and a sense that in Egypt the boundary between the past and present is at times rather thin. In his poem “To Helen,†Edgar Allen Poe epitomized classical civilizations with these lines: “To the glory that was Greece, And the grandeur that was Rome.†Is there a single word that captures the spirit of ancient Egypt in a similar way?

In addition to the works mentioned above, see Lucie Duff Gordon’s Letters from Egypt (many editions), Flaubert in Egypt (1979), and Florence Nightingale’s Letters from Egypt—A journey on the Nile (1987).

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our