The Recent Troubles at Lascaux

by Heather Pringle

August 1, 2008

For decades, outsiders have criticized the French for their Fawlty Towers approach to protecting and preserving the exquisite Paleolithic cave art of the Dordogne. As early as the late 1930s, for example, archaeologists in the German research institute, the Ahnenerbe, complained about the lax attitude of French authorities. “The named caves,†wrote Assien Bohmers at the time, “are owned by farmers, or managed by farmers, who don’t have the faintest idea about the cultural value of the rock art.†Bohmers thought the answer lay in German efficiency: he proposed that the Ahnenerbe, a Nazi organization, take control of the great cave paintings and their preservation—a plan that Nazi officials would have surely acted upon if Germany had won the war.

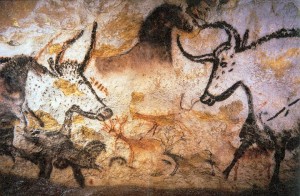

Since then, outside observers have often disparaged French attempts to protect the great paintings of Lascaux cave. In the late 1950s, green lichen bloomed on the walls of Lascaux, endangering the great paintings of stampeding horses and charging aurochs, which are thought to date from 17,000 to 15,000 years ago. So French officials closed the cave to the public. But in 2001, a white mold appeared, invading the cave and pocking the paintings. French authorities turned to fungicides. Now, to the dismay of everyone, some 70 black and grey fungal blotches—reportedly the size of human hands—have sprouted on Lascaux’s celebrated walls.

Alarmed, the UNESCO world heritage committee has stepped in, threatening to place Lascaux on its list of endangered cultural sites of global significance – a huge embarrassment for the French government, which prides itself on its love of culture and art. UNESCO has given French officials six months to find a solution to the latest fungal problem. In the meantime, it wants to send a group of independent experts to inspect the site.

This independent delegation may well emerge with valuable new recommendations for the preservation of Lascaux. I sincerely hope it does. But I think we are overlooking a basic archaeological truth in all this critical fire: it can be brutally difficult to rescue and save organic materials once preserved in an ancient sealed environment. I have seen many examples of this over the years. When researchers first retrieve human mummies from their natural or man-made tombs, for example, the bodies often appear in exceptional condition. But they swiftly deteriorate when separated from the precise environmental conditions that maintained them for hundreds or thousands of years.

Now imagine the immense difficulties that French officials face in trying to preserve the organic pigments of Lascaux’s art. Lascaux cave is a complex ecosystem and it has undergone nearly 70 years of major renovations—an enlarged entrance, a stairway, concrete flooring and two different air-conditioning systems, to name but a few alterations. No wonder the French are now tearing out their hair as they try to replicate the cave’s original environmental conditions or at least restore an ecological balance. “Each time we try to resolve one problem, we create another,†admits Marie Anne Sire, a French restoration expert who coordinates work at Lascaux.

I think we do the French experts a disservice to see them as the archaeological equivalent of Basil Fawlty. Lascaux is a daunting preservation problem, one that will not likely lend itself to easy solutions.

Lascaux photo courtesy of Prof Saxx.

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our