The Pleasures of the Field

by Heather Pringle

June 12, 2009

It’s often said that gardeners live entirely for the brief months of summer. All winter long, they thumb through dog-eared seed catalogs, poring over the pages for new varieties or obscure heritage plants that will yield the perfect tomato or the most fragrant sweet peas. In spring, they count the days until the last frost, anxious to see the first rows of tiny green shoots stretching down beds of rich black soil.

It’s often said that gardeners live entirely for the brief months of summer. All winter long, they thumb through dog-eared seed catalogs, poring over the pages for new varieties or obscure heritage plants that will yield the perfect tomato or the most fragrant sweet peas. In spring, they count the days until the last frost, anxious to see the first rows of tiny green shoots stretching down beds of rich black soil.

Many archaeologists live for the summer, too. They spend the dark days of winter in the lab, patiently sorting through and cataloguing artifacts and analyzing realms of data—the necessary work of archaeology required by any truly professional dig. But there’s a certain magic about the summer field season, a heady blend of freedom, discovery, high-spirited adventure, and intense camaraderie that is virtually impossible to resist.

I love heading into the field with a team—never knowing what to expect or what the season will reveal, never quite sure who my companions really are. Some field seasons are tests of personal character— in the Arctic, for example, where hungry polar bears lurk around base camps searching for a meal, or in the Subarctic, where clouds of blackflies and mosquitoes line up to take blood samples. One of the greatest displays of macho I’ve ever seen was in the northern Yukon, where Canadian archaeologist Jacques Cinq-Mars, the editor of Palanth, disdained Deet and all other mosquito repellents, and went about his fieldwork covered from head to toe in a black buzz of mosquitoes. I still don’t know how he managed this kind of zen. I had to douse myself repeatedly  in Deet and don a mosquito-netted hat to get through the week. But Cinq-Mars insisted on eating well in the field, and I soon realized that he is the Jamie Oliver of Yukon archaeology. He makes the best bannock bread—sprinkled with sugar and cinnamon—I’ve ever tasted.

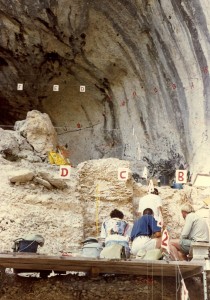

Other field seasons are a pure, undiluted joy. One of the finest experiences I ever had was in the south of France, in Provence, where a field school led by Serge Lebel, an archaeologist at the University of Quebec at Montreal, was excavating a rockshelter inhabited some 35,000 years ago by Neanderthals. The team was based in the perfect field camp—a rambling old Provençal farmhouse with a huge harvest table where the crew gathered for meals. And early each morning, before the cicadas began to sing, we drove down to the site in a couple of beaten-up looking cars, with the Clash blasting out the open windows.

I remember many things about that field season—the famous fields of lavender, the great wine we quaffed each night at dinner, the coolness of the rockshelter at mid-day, the square I was temporarily assigned, the wooly rhinoceros bones that littered it. But one day in particular stands out in my mind. Lebel had been excavating at Bau de l’Aubesier, as the site is known, for years, searching diligently for even the smallest trace of hominid remains. Everyone on the crew knew this, and each of us desperately wanted to be the first to find them. I had the great good fortune to be there the day a team member found a hominid tooth—which later proved to be Neanderthal—and I took part in the emotional celebration that followed. Lebel had stowed away a crate of some very fine French champagne for just that occasion, and team member after team member stood up and toasted him and the ancient Neanderthal whose tooth they had recovered. It was one of the best parties I have ever attended.

Most archaeologists experience a day like this at least once in their careers, and the luckiest experience it more often. This kind of shared euphoria is unforgettable, and I suspect that such experiences go a long way in explaining why archaeologists so often tend to marry other archaeologists. Field seasons are bonding experiences.

I know that many archaeologists are now in the field, making good on all the plans they drew up so painstakingly last winter. But I’d love to hear from those who have a moment. What was your best field season and what made it so great?

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our