TB or not TB

by Mark Rose

July 30, 2009

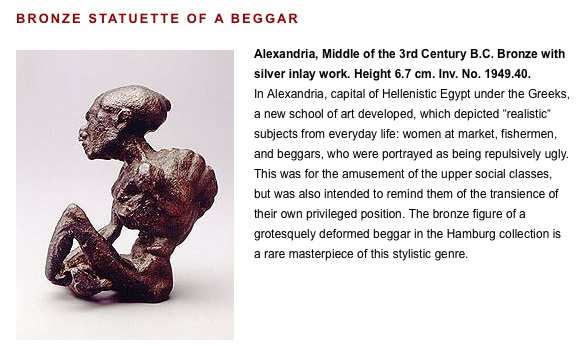

More than beauty is in the eye of the beholder. In fact, our training can determine what our “eye†sees. I was reminded of this while editing an article by Lois Wingerson about the evidence for ancient tuberculosis (see our September/October issue, which should be out in the next week or so). Many years ago, I happened to show a photograph of a small bronze figurine to a paleopathologist, Della C. Cook, at Indiana University. The bronze, without solid contextual evidence but likely from Alexandria and dating to the middle of the third century B.C., is in the collection of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg. The photo of it I saw was published in a book called Master Bronzes from the Classical World, a catalogue of an exhibition that traveled the U.S. in 1967–1968. The author of the book, with S. F. Doeringer, was David Gordon Mitten, a curator at Harvard University Art Museums and specialist in classical bronzes.

More than beauty is in the eye of the beholder. In fact, our training can determine what our “eye†sees. I was reminded of this while editing an article by Lois Wingerson about the evidence for ancient tuberculosis (see our September/October issue, which should be out in the next week or so). Many years ago, I happened to show a photograph of a small bronze figurine to a paleopathologist, Della C. Cook, at Indiana University. The bronze, without solid contextual evidence but likely from Alexandria and dating to the middle of the third century B.C., is in the collection of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg. The photo of it I saw was published in a book called Master Bronzes from the Classical World, a catalogue of an exhibition that traveled the U.S. in 1967–1968. The author of the book, with S. F. Doeringer, was David Gordon Mitten, a curator at Harvard University Art Museums and specialist in classical bronzes.

So, what do an art historian and a paleopathologist see when they look at the same artifact? On page 23 of Master Bronzes, we read this:

The remorseless, almost repulsive realism with which the hunchback is endowed identifies him as a crippled beggar or fisherman who eked out bare subsistence on the street-corners and waterfronts of Hellenistic ports like Alexandria, the city which played a leading role in creating and maintaining genre subjects like these as a principal current in Hellenistic art.

Cook had a different take: the figure showed someone devastated by tuberculosis, with characteristic collapsing of the vertebrae.

While working on the tuberculosis story, I took the opportunity to revisit this bronze, directing two more scholars with strong credentials in the study of ancient tuberculosis to the museum’s website, where they could see a photograph of the bronze and read a description of it that largely matches that from Master Bronzes. Have a look yourself at www.mkg-hamburg.de/mkg.php/en/sammlungen/antike/~P6.

The museum says:

In Alexandria, capital of Hellenistic Egypt under the Greeks, a new school of art developed, which depicted “realistic” subjects from everyday life: women at market, fishermen, and beggars, who were portrayed as being repulsively ugly. This was for the amusement of the upper social classes, but was also intended to remind them of the transience of their own privileged position. The bronze figure of a grotesquely deformed beggar in the Hamburg collection is a rare masterpiece of this stylistic genre.

The paleopathologists have a different view. Arizona State University anthropologist Jane Buikstra, co-author with Charlotte A. Roberts of The Bioarchaeology of Tuberculosis: A Global View on a Reemerging Disease (2003), says “that looks like the typical kyphotic spine of TB.†And Mark Spigelman of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem responds, “a gibbus malformation of his spine typical of…TB vertebral body collapse.†Okay—the figurine shows a man dying of tuberculosis.

What does it mean that we have two very different views of the same object? While the art historians clearly missed the boat in terms of what the figurine depicts, the paleopathologists would likely not be able to address social contexts, such as whether this was for the “amusement of the upper social classes†or perhaps meant to ward off a terrible affliction. Ultimately, I think art historians need to reach out to scholars with other areas of expertise when confronted with objects such as this. (I’ve noted myself chronic misidentifications by art historians of various marine critters depicted in ancient works, from frescoes to vase paintings.) But the real lesson is that if we want to get the most out of what we dig up today (or find in museum basements), we need to bridge the gaps between academic subjects and take a larger view.

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our