Big Oil and China’s Past

by Heather Pringle

November 28, 2008

People often ask me why I write about archaeology.  I can see from their puzzled looks that they think of archaeology as something irrelevant, so musty and obscure and distant from modern life that it scarcely warrants serious attention from a journalist. Indeed, whenever I have a conversation with my older brother, a successful lawyer, about book ideas I have, he looks at me with genuine concern. “Do you think anyone will be interested in that?†he asks in bewilderment, putting into words something that others, perhaps more reserved, leave unspoken.

People often ask me why I write about archaeology.  I can see from their puzzled looks that they think of archaeology as something irrelevant, so musty and obscure and distant from modern life that it scarcely warrants serious attention from a journalist. Indeed, whenever I have a conversation with my older brother, a successful lawyer, about book ideas I have, he looks at me with genuine concern. “Do you think anyone will be interested in that?†he asks in bewilderment, putting into words something that others, perhaps more reserved, leave unspoken.

Over the years, I have seen how much archaeology can tell us about who we are today and the forces that shape the world around us.  The past is not dead and buried: it lives on in many surprising ways, as I was reminded recently by a fascinating article in The New York Times about the famous Xinjiang mummies and China’s petro politics.  For those of you who missed the article, or the chapter I wrote about these mummies in my book, The Mummy Congress, here’s the story in brief.Â

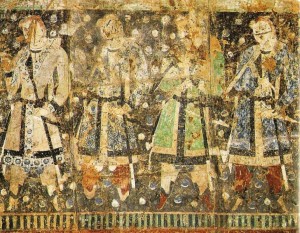

During the 1970s, while surveying along proposed oil pipeline and railway routes in China’s Xinjiang province, Chinese archaeologists came across a trove of some 200 naturally mummified bodies, the oldest of which dated back some 4100 years. These weren’t at all like other Chinese mummies. Some wore Celtic plaid woolens. Others sported familiar forms of western haberdashery: conical black witches’ hats, tam-o’-shanters and Robin Hood style caps. And many possessed locks of blond, red and auburn hair.

In the late 1980s, a museum in Xinjiang’s capital hosted a small show on the curious finds. By chance, a prominent Sinologist from the University of Pennsylvania, Victor Mair, was there at the time, leading a tour group of westerners.  Mair ducked into the exhibit for a look, and was stunned by what he saw. The mummies looked very much like migrants from the West who had settled in the northwesternmost region of China at the height of the Bronze Age. Mair was very surprised. Most scholars believed that the earliest contacts between China and the West took place much, much later, in the second century B.C. So Mair decided to investigate, collaborating with archaeologists and embarking on a two-decade-long study has focussed the world’s attention on these stunning finds.  Â

But Mair’s dogged research wasn’t much appreciated by Chinese authorities—for reasons quite apart from archaeology. China currently depends on foreign oil for nearly half of its needs, but Xinjiang is rich in reserves. Beneath its barren deserts lie an estimated 20.9 billion tons of oil, which the Chinese government is desperate to develop.  There’s a hitch, however.  Xinjiang is home to a rebellious ethnic minority: a Moslem, Turkic-speaking people known as the Uyghurs. The Uyghurs have long wanted their own country, briefly founding two republics in the 1930s and 1940s that later fell under Chinese control. Today tensions continue: in 2007, for example, Chinese police raided a camp of Uyghur insurgents, killing 18.

The Uyghurs now claim the western-looking mummies as their ancestors, and offer them as proof that Xinjiang is really a Uyghur homeland, not a legitimate Chinese province. But the Uyghurs are likely stretching a point: most archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that they arrived much later in the deserts of Xinjiang. Â

Mair yearns to do thorough, up-to-date DNA testing on the mummies to trace their ancestry and settle the matter. But Chinese authorities would like nothing better than to stuff the genie back in the bottle. They have refused to allow him to take mummy tissue samples out of China, preferring to give the politically charged work of DNA testing to Chinese scientists. In 2007, Jin Li, a genetist at Shanghai’s Fudan University, reported that DNA tests had shown that the Xinjiang mummies were of East Asian or South Asian origin–something that Mair’s research firmly refutes.Â

I once spent a week in Shanghai with Mair as he jockeyed for permission from museum officials there to take samples from the mummies. I’ve never seen such delicate, intense negotiations. If the ancient dead are so irrelevant, why do the living care about them so intensely? And why do powerful governments shrink from the stories they can tell?Â

Â

Â

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our