Money, Money, Money

by Heather Pringle

June 19, 2009

On a radiantly clear, late summer day in 1991, two German hikers were descending from the summit of a mountain in the Italian Southern Tyrol, when they spotted something odd protruding from the ice in the distance. Helmut Simon, a caretaker from Nuremberg, and his wife Erika, wondered if it was a discarded doll, but as they pair wound down the slope, they realized that it was a human being. “We thought it was a mountaineer who died here,†recalled Erika Simon later in a conversation with the late Konrad Spindler, an archaeologist at the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg. “We were shocked and didn’t touch the body.â€

On a radiantly clear, late summer day in 1991, two German hikers were descending from the summit of a mountain in the Italian Southern Tyrol, when they spotted something odd protruding from the ice in the distance. Helmut Simon, a caretaker from Nuremberg, and his wife Erika, wondered if it was a discarded doll, but as they pair wound down the slope, they realized that it was a human being. “We thought it was a mountaineer who died here,†recalled Erika Simon later in a conversation with the late Konrad Spindler, an archaeologist at the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg. “We were shocked and didn’t touch the body.â€

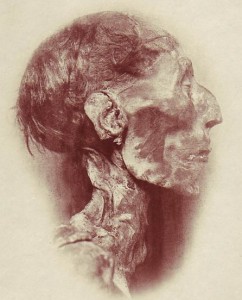

The Simons reported their find, and the cadaver proved to be that of a 5300-year-old man, later dubbed Oetzi—the oldest known naturally preserved mummy in Europe. Since then, Oetzi has become the subject of hundreds of major scientific papers and books, the star of countless newcasts and television documentaries and the prime exhibit in a major museum in Bolzano, Italy. And as I discovered in a fascinating little news story this week, the find was also the subject of a 15-year legal battle launched by Gert and Erika Simon. The two mountaineers wanted a cut of the enormous revenue generated by Oetzi.

Mummies, after all, are big business. The bodies of the everlasting dead—whether they are bog bodies, Egyptian mummies, or Scythian princesses—draw large, fascinated crowds when exhibited in museums. It is one thing to read about the ancient cultures or marvel at the beauty of their architecture and statues: it is quite another to gaze at the face of a long-dead pharaoh or an Iron-Age teenager. As humans, we daily read the faces of the strangers we encounter for hundreds of subtle clues about who they are: many of us want to do the same with the ancient dead.

The Simons’ determined legal battle shed light on something rarely openly discussed in the museum community: how the discovery of a major new mummy can bring millions of dollars annually into a city or town. According to estimates that the Simons filed in court, restaurateurs, hotel owners and souvenir sellers in Bolzano alone rake in nearly $ 5.5 million annually from the visitors who travel to the town specifically to see Oetzi. And this does not even begin to account for the revenues from museum ticket sales, books, documentaries, sourvenirs, and website advertising. (To get a sense of how extensive these can be see http://archive.archaeology.org/online/features/bog/exhibit.html )

The court has decided that Erika Simon will now receive a finder’s fee of some $210,000, and authorities in Italy have agreed to pay up. (Simon’s husband Gert died five years ago in an accident.) The decision, of course, raises many ethical issues. Should museums be in the business at all of displaying the bodies of the ancient dead? Who has the right to determine what should happen to these cadavers? Descendants? Governments? Archaeologists? And should finders receive any payment at all for turning over such bodies to authorities?

I think we need to continue to debate and think about these issues. I personally think that paying a finder’s fee to Erika Simon was a big mistake. It sets a legal precedent, one which may further encourage looters to go out and look for other similarly preserved human remains.

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our