Happy New Year–1910!

by Mark Rose

January 2, 2010

Well, we’ve rolled the calendar over once again. Here, at the start of 2010, I thought it would be fun to take a look back at some of the archaeological stories that were in a century ago. Lacking a time machine, I turned to the News in History website (www.newsinhistory.com). This is one of my favorite websites these days. It offers unrestricted access to 200 years of American newspapers for a modest $8 or $9 per month, so I file it under research and cheap entertainment.

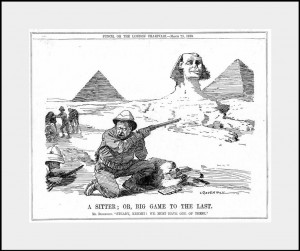

Teddy Roosevelt stalks the Sphinx

What were the big stories in 1910? For celebrity factor, the prize was won by Teddy Roosevelt’s trip to Egypt, family in tow–Teddy “Rides Camel-back Over Bygone Civilization,†according to one headline. The Roosevelts viewed the Sphinx by moonlight, of course, and saw Sakkara, but “the privacy of the movements of the Americans was invaded during this tour by a moving picture man, who focused his machine upon them and rolled off yard after yard of films.â€

There were legitimate discoveries, too. A long article, picked up in the U.S. papers from the London Times, tells of the discovery of the shrine of Aphrodite in Cyprus by “Dr. Koritzky, a German Archaeologist.†A brief note acknowledges a Hungarian scholar’s discovery of the Roman city of Porolisum in Transylvania. In an article special to the New Orleans Times-Picayune, readers learned of Count M. de Periguy’s finding of a “buried city†in Guatemala where he had been searching for “Aztec ruins.†The story notes that “The natives tell many strange tales of these old cities, they have been the quest of many adventurers, and there is no doubt that the country offers many inducements for treasure seekers and men of science.â€

Buried cities were apparently the sought-after-item by archaeologists in 1910. Edgar L. Hewitt found “Buried Cities in the Rio Grande.†The author of the article, however, doesn’t seem certain if it was just one or many such sites, describing: “The discovery of a buried city in New Mexico…and of a vanished people, who lived like rats in holes along the cliffs of an almost inaccessible canyon.†Elsewhere in the Southwest, the Smithsonian’s J.W. Fewkes was finding 500-year-old sites in a “Strange Region Up in Navajo Country of Arizona.†Work for the Palestine Exploration Fund by Duncan Mackenzie is outlined in a report titled “Buried Cities Sought: Archaeologist to Explore Holy Land on Enormous Scale.†As with the search for the buried city in Guatemala, we are told that “natives†play a role here: “Fifty natives are now being collected for excavating and sifting the soil on the site of lost cities.†In another newspaper account, we are told that archaeologist Mrs. Zella Nuttall is en route to “uncover ruins†in Mexico, though it is unclear if these constitute a buried city or if “natives†will be involved.

Newspapers covered more questionable endeavors as well, lauding Paul Pelliot (“the explorer and archaeologistâ€) for hauling back to Paris from Chinese Turkestan some 6,000 ancient manuscripts. William Niven’s discovery of vestiges of Atlantis in Mexico—a blatant hoax—rounds out the parade of finds for 1910.

There were also moral lessons to be learned from archaeology that year. The Chicago Record-Herald provided the uplifting story “Teach A Boy To Use His Spare Time.†Wise use of spare time, learned young, would be of help throughout life, according to the author, who provides a number of examples, including Sir John Lubbock, whose careful application of spare time raised him from being a banker to “a great archaeologist.†Another kind of moral lesson was suggested by the archaeological scandal of 1910: the divorce of archaeologist Charles F. Lummis, who apparently recorded his affairs in a diary he kept in Greek and Spanish. But somehow Lummis–“a picturesque figure, as he always dresses in corduroy, with a sombrero hat trimmed with snake rattles on the band–overlooked the fact that his wife could read Spanish.

On the humorous side, one can sympathize with the journalist who had to write an enthusiastic piece about an Egyptian inscription going on display in a local museum in Grand Forks, North Dakota. The difficulty? Although we are told it is a “valuable antiquity,†the fact is “A French archaeologist has translated it, but the translation has not arrived yet.â€

An inquisitive spirit marks these newspapers accounts, and even if the details are a bit off, we can applaud the attempt to describe the wonders of prehistory and archaeology to the public of that era. Reporters did their best to paint a picture that would capture the imagination, as did this one describing Neanderthals in the Duluth News-Tribune:

The limbs are short compared to the length of the trunk; their proportion is comparatively that which we observe in children. The incurvature of the legs proves that this young man must have walked with bent knees like the old men of our own day. With bodies probably covered with hair, he and his fellows prowled in small hungry groups, in countries rich in game but poor in vegetable food. A leather belt with which he tightened his stomach during days of famine was likely his only garment. His weapons were rudimentary, a mere cudgel, perhaps, also a spear with the point hardened by fire, which this primitive being knew how to procure by rubbing together two pieces of wood; and tools of flint, which he was already making.

A hundred years from now, will the articles in ARCHAEOLOGY be thought of as accurate–or humorous–as those from 1910 appear to us now?

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our