Drowned Worlds

by Heather Pringle

July 25, 2008

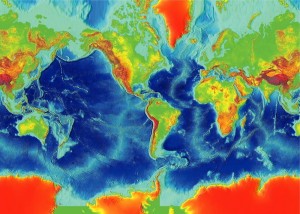

A fascinating article on Doggerland that appeared in the July 10th issue of Nature reminds me yet again that the real Terra Incognita in archaeology is not on land at all: it lies under the world’s oceans. Doggerland, as you may know, is the name of a vast plain that joined Britain to Europe for nearly 12,000 years, until sea levels began rising dramatically after the last Ice Age. Taking its name from a prominent shipping hazard—Dogger Bank—this immense landbridge vanished beneath the North Sea around 6000 B.C.

A fascinating article on Doggerland that appeared in the July 10th issue of Nature reminds me yet again that the real Terra Incognita in archaeology is not on land at all: it lies under the world’s oceans. Doggerland, as you may know, is the name of a vast plain that joined Britain to Europe for nearly 12,000 years, until sea levels began rising dramatically after the last Ice Age. Taking its name from a prominent shipping hazard—Dogger Bank—this immense landbridge vanished beneath the North Sea around 6000 B.C.

Like all landbridges, Doggerland seems to have been a pretty busy thoroughfare for ancient hunters and gatherers. But archaeologists hardly gave it a thought until 2002. In that year, a small group of British researchers laid hands on seismic survey data collected by the petroleum industry in the North Sea. They put it to work in an ingenious way, reconstructing a soccer-field-sized patch of Doggerland. Since then, interest in this drowned world has grown dramatically. A University of Wolverhampton computer engineer, Eugene Ch’ng, for example, is building a virtual-reality simulation of an ancient Doggerland river valley during the Mesolithic period, which began 10,000 years ago. This longlost world is complete down to patches of stinging nettles indicated by pollen records from nearby regions, and painstaking recreations of Mesolithic huts and hide-tanning racks.

Such reconstructions are more than just displays of scientific shock and awe. By visualizing the continental shelves in detail, archaeologists hope to home in on promising landscapes for costly underwater exploration and excavation. Doggerland, for example, may have been rife with Mesolithic sites, and archaeologists are immensely keen to see how bands from this period made use of the landscape and adapted to rising sea levels.

And here’s the key point. Doggerland is currently in the spotlight, but it is by no means the only lost world attracting scientific attention. Canadian researchers have mapped drowned river deltas and forests along the west coast of British Columbia in hopes of discovering campsites of Ice Age coastal mariners. And American archaeologists have charted and explored drowned river valleys in Florida’s Apalachee Bay, collecting from their slopes more than 4000 pieces of chipped stone as well as bone fragments from giant sloths and other Ice Age animals.

Underwater research is incredibly expensive, but it’s becoming increasingly clear that the future of archaeology lies at least partly under the waves.

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our