Check Your Venus Fantasies at the Door, Gentlemen

by Heather Pringle

May 15, 2009

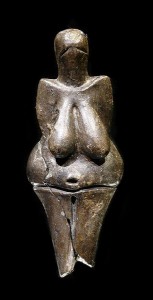

Are the Venus figurines really the Paleolithic version of Linda Lovelace? I asked myself this question this week after reading a spate of steamy articles announcing the discovery of the Venus of Hohle Fels.  In case you missed it, an archaeological team led by Nicholas Conard at the University of Tübingen excavated a truly remarkable mammoth-ivory statuette  from a German cave, Hohle Fels.  Dated to at least 35,000 years ago, this female figurine is likely the earliest known piece of figurative sculpture in the world.Â

Are the Venus figurines really the Paleolithic version of Linda Lovelace? I asked myself this question this week after reading a spate of steamy articles announcing the discovery of the Venus of Hohle Fels.  In case you missed it, an archaeological team led by Nicholas Conard at the University of Tübingen excavated a truly remarkable mammoth-ivory statuette  from a German cave, Hohle Fels.  Dated to at least 35,000 years ago, this female figurine is likely the earliest known piece of figurative sculpture in the world.Â

But what set male archaeologists and journalists alike off, it seems, was its portrayal of female sexuality. The Venus of Hohle Fels lacks a head and face, but possesses large, firm breasts and what appears to be an exaggerated and detailed vulva.  And these features reportedly  prompted archaeologist Paul Mellars, currently a visiting scholar at Stony Brook University in New York, to remark  in an interview with ScienceNOW that the “little statuette was sexually exaggerated to the point of being pornographic.†(The article bore a jaw-dropping headline: “The Earliest Pornography?â€)  Another story, this time by an Associated Press reporter, quoted Mellars as apparently saying: “These people were obsessed with sex.â€Â Â

All this makes for a very entertaining archaeology story,  sexier by far than the world’s earliest cultivated rice, say. But what these articles don’t tell you is that Mellars’ ideas are highly controversial. Many prominent female archaeologists, who have carefully studied some or all of the more than 100 known Venus figurines,  reject the view that these Paleolithic figurines were carved by and for men at all.

The idea of the figurines as early pornography is, in my opinion,  a dated one,  deriving as it does from a time when early anthropologists observed only male hunters carving stone and ivory. Women, early researchers assumed, lacked the physical strength to carve such hard materials. But a detailed search of ethnographic sources by Linda Owen, an archaeologist at the University of Tübingen, in the 1990s revealed the opposite: women from a number of Arctic and Subarctic societies did indeed work stone and ivory on occasions.Â

And evidence from other leading archaeologists clearly suggests that the Venus figurines once belonged to a secret world of ceremony and ritual. Olga Soffer, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, and Pamela Vandiver at the University of Arizona, spent years studying the famous ceramic Black Venus and other similar figurines—both human and animal—found at the famous Paleolithic site of Dolni Vestonice in the Czech Republic.  The two archaeologists discovered something extremely interesting. Both the Black Venus and the other statuettes were made from a clay resistant to thermal-shock fracturing. Yet many of the figurines, including the Black Venus, bear the distinctive fracturing patterns of thermal shock.  (By contrast,  the simply shaped and fired clay pellets at the site do not.) Why?Â

Soffer has suggested—very intriguingly I think—that the little statuettes were part of a ritual to discern what the future held. The Paleolithic kilns at Dolni Vestonice are located away from the dwellings, a common pattern for ritual structures.  And the figurines would have lent themselves well to divination rites. “Some stuff is going to explode,†Soffer told me once in an interview. “Some stuff is not going to explode. It’s evocative, like picking petals off a daisy. She loves me, she loves me not.â€Â

And it’s even possible that Paleolithic ceremonialists saw significance in the pattern of fracturing. In historic times in North America,  Soffer pointed out, Cree ritualists placed the shoulder blade of a desired animal in a hearth.  As the bone heated, cracks formed and beads of fat dripped into the fire. Cree ritualists predicted that hunters would find game if they journeyed in the directions indicated by the cracks.

Soffer is by no means the only female Paleolithic archaeologist who rejects the idea that the Venus figurines were the products of men’s sexual fantasies.   Margherita Mussi, an archaeologist at the University of Rome-La Sapienza, and many others have also seen strong ritual connections to the figurines. But no journalist seems to have elicited a quote from them, and so a very old idea about the figurines has been resuscitated –without challenge—in the popular press.     Â

Â

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our