The Sacred Fingers of Galileo

by Heather Pringle

November 27, 2009

I have been thinking a great deal this week about the rediscovery of Galileo’s fingers in a glass vase in Italy. On the surface the story seemed, well, ghoulish. Who would want to desecrate the body of the famous Italian scientist by severing his thumb and middle finger after death? But as I read the news articles,  and thought about the mummies of saints I once studied in Italy, I realized what had happened to Galileo and why. And the connection tells us something wonderful and quite touching about religion and science.

I have been thinking a great deal this week about the rediscovery of Galileo’s fingers in a glass vase in Italy. On the surface the story seemed, well, ghoulish. Who would want to desecrate the body of the famous Italian scientist by severing his thumb and middle finger after death? But as I read the news articles,  and thought about the mummies of saints I once studied in Italy, I realized what had happened to Galileo and why. And the connection tells us something wonderful and quite touching about religion and science.

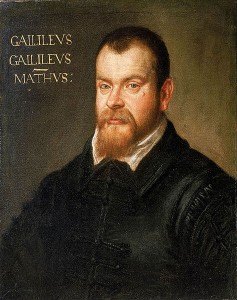

Before I turn to that, however, let me first sum up the news story for you. A private collector recently approached the director of the Museum of the History of Science in Florence with an unlabeled vase containing two wizened human fingers and a human tooth. The collector had purchased the vase at an auction, suspecting that it contained the fingers of the Galileo Galilei, the first man to gaze at the night skies through a telescope. After poring over detailed historical documents, the museum director, Paolo Galluzzi, authenticated the find. The middle finger, thumb, and tooth all belonged to the famous scientist, who died in 1642 after spending the last eight years of his life under house arrest.

Galileo, as you may recall, was tried on suspicion of heresy by the Inquisition in Rome in 1633. He had amassed conclusive evidence that the earth revolved around the sun—evidence which refuted Catholic dogma that the earth was the center of the universe.  But the Inquisition would have none of it. It convicted Galileo and ordered him to state that he “abjured, cursed and detested†this heresy. This Galileo sadly did.

In 1737, ninety-five years after Galileo died, devoted admirers moved the scientist’s body to a grand tomb in Florence’s Santa Croce Basilica, near where Michelangelo rested. But before they laid Galileo’s remains to rest, an Italian marquis severed the scientists’ fingers and tooth and placed them in a glass vase for preservation.

As it turns out, there was a very important Catholic precedent for the marquis’s behavior.  Let me explain.  When the Vatican canonized a new saint,  priests or nuns removed individual’s body from its burial place in a church crypt. Sometimes the chemical and climatic conditions in Italian church crypts were exactly right for natural mummification. So the saint that emerged from these crypts looked exceptionally lifelike. Devout Catholics called these saints the Incorruptibles, and they viewed their bodily preservation as further proof of holiness.  They snipped off small pieces from these saints for holy relics that could be sent to other churches.  Then they put the bodies on display in glass-sided reliquaries in churches.

Galileo’s admirers must have been much struck by the state of his body when they moved it in March 1737. Parts of it, if not the entire corpse, had undergone natural mummification. (Indeed, one photo published this week shows both withered flesh and a fingernail on one of the digits.)

To some in attendance that day in 1737,  Galileo appeared as an Incorruptible, a new kind of saint—a saint for science.  They would never be allowed to display his body in Santa Croce Basilica, however:  the Vatican would have no part of it.  So the Italian marquis did what generations of devout Catholics did. He took the most sacred parts of Galileo’s body—the fingers the scientist used to hold his pen and adjust his telescope—as holy relics, and stored them in a glass container.

Some might call this a final terrible irony—that a scientist so persecuted by the Catholic Church should have been honored like a saint. But I think what happened to Galileo is a kind of miracle—science and religion at peace at last.

Comments posted here do not represent the views or policies of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our

Heather Pringle is a freelance science journalist who has been writing about archaeology for more than 20 years. She is the author of Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead. For more about Heather, see our