It was not so very long ago that many archaeologists regarded the Ancestral Puebloan people–or the Anasazi, as researchers once called them–as a rather peaceful, mystical group of astronomers, artists, priests and farmers. They based this idea largely on their observations of modern Puebloan peoples: the Hopi, the Zuni and others who lived in traditional pueblos, such as Taos, and who often lived quiet lives of ritual and spirituality.

It was not so very long ago that many archaeologists regarded the Ancestral Puebloan people–or the Anasazi, as researchers once called them–as a rather peaceful, mystical group of astronomers, artists, priests and farmers. They based this idea largely on their observations of modern Puebloan peoples: the Hopi, the Zuni and others who lived in traditional pueblos, such as Taos, and who often lived quiet lives of ritual and spirituality.

But in the early 90s, some Southwestern archaeologists began questioning this received wisdom. David Wilcox, an archaeologist at the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, hypothesized that the rulers of Chaco Canyon, a massive Ancestral Puebloan site, commanded a small army and demanded tribute from their southern neighbors, slaughtering any who didn’t comply. As evidence, Wilcox pointed to charnel pits excavated in dozens of Ancestral Puebloan sites dating to the late 10th and early 11th century C.E.: these pits looked like mass graves from a war zone.

At first most Southwestern archaeologists just shook their head and smiled at Wilcox’s ideas. Â But evidence of very nasty times in the ancient Southwest began to accumulate. Â Physical anthropologist Christy Turner, now a professor emeritus at Arizona State University, and others detected traces of extreme violence and cannibalism on human bones unearthed at 40 different Ancestral Puebloan sites. Â Such acts of cannibalism, Wilcox suggested, were political messages, deliberate desecration of the dead as a warning to others.

This month, researchers added yet more dark shading to the picture in a paper published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. At a site known as Sacred Ridge in Colorado, Jason Chuipka, an archaeologist at Woods Canyon Archaeological Consultants, and his colleagues unearthed 14,882 human skeletal fragments–the remains of deliberately mutilated Ancestral Puebloan inhabitants–as well as two-headed axes smeared with human blood residues. Â The dead dated to the late 8th or early 9th century, Â a time when the first Ancestral Puebloan villages were forming.

To Chuipka and his co-author James Potter, an archaeologist at SWCA Environmental Consultants in Broomfield, Colorado, the evidence suggested that the inhabitants of Sacred Ridge–men, women and children–were singled out for a particularly terrible form of violence: Â ethnic conflict.

So what to make of all this?  Why such a radical shift in our vision of the Ancestral Puebloan people? When I began thinking about this,  I came up with two things.  First of all,  physical anthropologists today know much more about the osteological indicators of warfare and cannibalism than they did thirty years ago.  So they have a much clearer idea of  what to look for.

But the second thing goes to the very heart of archaeology itself. Journalists and other members of the public ask archaeologists all the time to explain what various artifacts and data mean.  We don’t really want to hear about 14,882 bone fragments.  What we want to know is what happened to all those bodies and all those people.  And our insatiable curiosity constantly forces archaeologists to interpret their findings, to make a story of them.

So archaeologists do what anybody else would do–they look for analogies in modern life. In the early 1970s, Â for example, when the Vietnam War raged, many researchers hypothesized that the collapse of the Classic Maya civilization was due to extreme warfare. In the 1980s and 1990s, they pointed to environmental causes, such as soil erosion. And today, many researchers ascribe the collapse to climate change, Â specifically a series of devastating droughts.

Probably all these factors played a part in the fall of the classic Maya civilization. But I find it interesting to think about the ways in which contemporary history contributes to prevailing archaeological hypotheses and interpretations. Â I personally think it’s very possible that some Ancestral Puebloan people were victims of ethnic cleansing. But would the archaeological community have taken this idea so seriously, Â had it not been for the intense media coverage of ethnic conflicts and cleansing in places like Bosnia, Rwanda and Sudan in recent years?

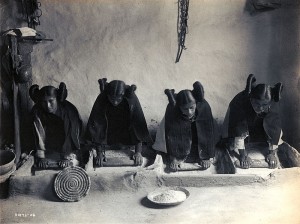

Photo of four young Hopi women milling grain by Edward Curtis.